The development and layout of Hastings and St Leonards owe much to turnpike roads built in and around the towns in the 18th and 19th centuries. This came to a climax in the late 1830s when two Acts of Parliament authorised the construction of a crucial network of roads in the Hastings area, including the A21 from St Leonards to Whatlington and the rival Battle Road through Hollington. And the shape of this network was decided by a few local business entrepreneurs.

Until the early 1830s there had been only two ways in and out of Hastings for long-distance travellers: by sea, or by ‘the London road’. This highway started at the top of the High Street, went up what is now called Old London Road and joined the pre-Roman trackway that ran inland to the north-west, following the contour lines to stay above the deep, wooded valleys of the Weald.

That trackway still exists today, first as the Ridge running from Ore out of Hastings, then becoming the A2100 into Battle. For many centuries before the 1830s, the main track to London ran north-east from Battle along what is now Mount Street through Whatlington to where the Royal Oak Inn and white church are just north of that village. From here the A21 sits more-or-less on top of this old London road, through Johns Cross and Robertsbridge and on to Flimwell, ignoring the modern bypasses.

The six miles of today's A21 south of Whatlington's Royal Oak Inn through the Harrow to Silverhill did not exist before the 1830s, and neither did today’s Battle Road in Hollington, or the A2100 north from Battle to Johns Cross.

It was the turnpike roads that transformed all this - but people had to pay to use them. The turnpikes began appearing in the early 1700s because the rapid growth of industry and commerce across Britain at that time meant that all through-roads like that from London to Hastings were being heavily used. But many of these roads had also become almost impassable in winter, being full of mud and ruts because of the increased use by heavy wheeled vehicles. Maintenance of the roads was poor because the legal responsibility for it fell on the shoulders of local parishes, who saw the roads system as unfair - why should local landowners subsidise passing businessmen and traders?

The urgent need for roads to be improved led to the creation of the turnpike system. From 1706 the government allowed landowners and other professional people to form turnpike ‘trusts’, by paying for their own Acts of Parliament. These gave the promoters the legal power to compulsorily purchase land and buildings to create their road. The trusts were corporate bodies which, for a set time, could take over an existing road or build a new one, and were ‘non-profitmaking’. But the promoters did not expect to profit from actually owning a road; they had their eyes on the new trade and property development that the turnpikes brought as spin-offs.

The law stated that trustees had to be owners of a significant amount of property. This meant they were often landowners who had a strong self-interest in turning their adjoining road into a turnpike, because it could increase the value of their property and generate more trade for them, while they would no longer have to pay for its upkeep. They also often made money by loaning the trusts large sums for capital works, which were repaid with a higher than usual interest rate.

But by turning roads into turnpikes the trustees were privatising public highways, where previously there had been unrestricted rights of way. A toll was levied on road users to pay for the routine maintenance. Everyone had to pass through tollgates, placed at regular intervals, with tollhouses standing alongside, where lived the gatekeeper who would extract the money from them. Pedestrians and local farm traffic were exempt; everyone else had to pay.

In 1753 many prominent Hastings figures - including the major landowners Edward Milward and John Collier - obtained an Act that allowed them to take control of the existing Hastings-London trackway via Battle and Whatlington, as far north as Flimwell.

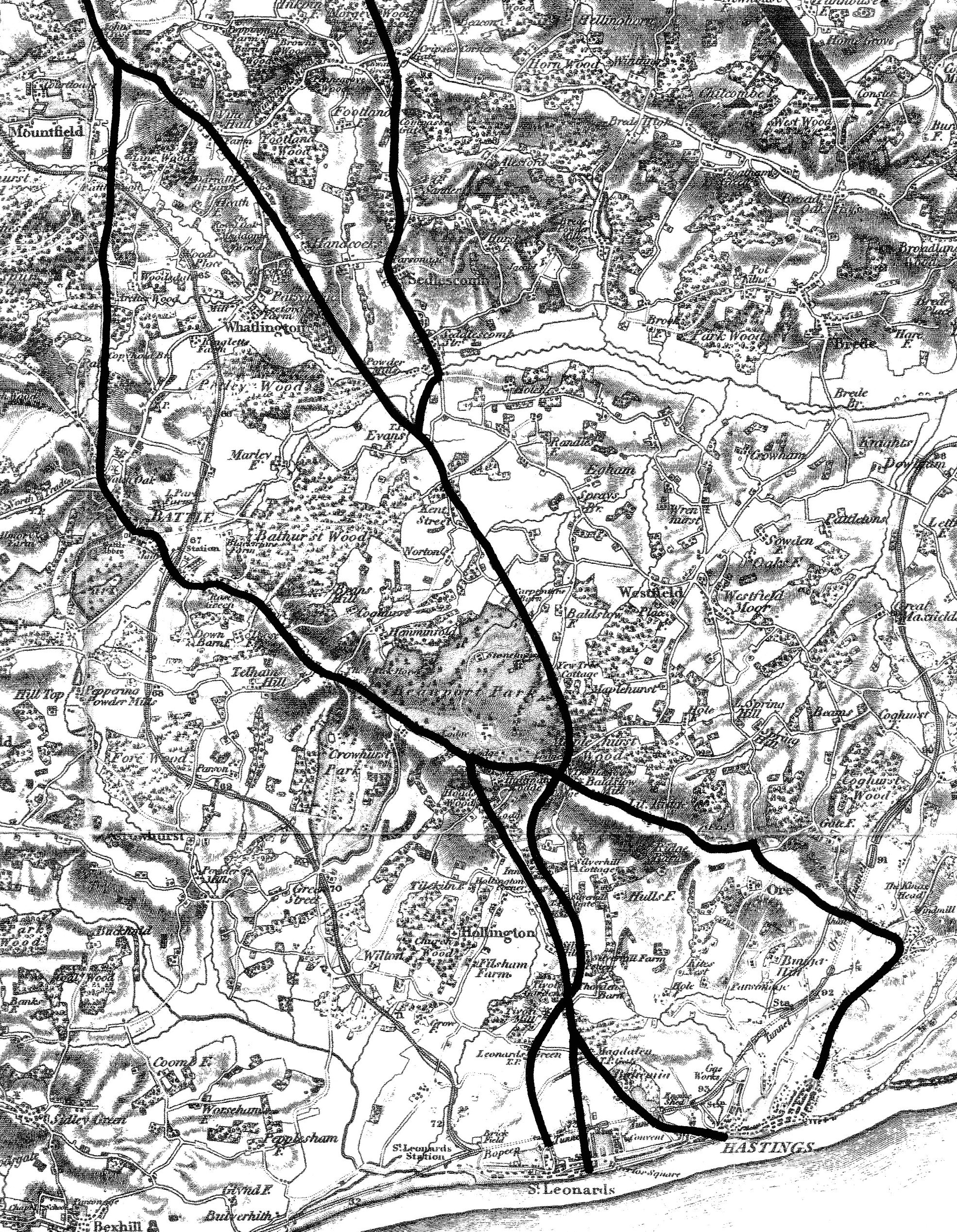

The 1753 Hastings-Flimwell turnpike road, highlighted on a mid-1830s map.

Work on the Hastings-Flimwell turnpike road began at the Hastings end. The first tollgate was put up in June 1753 at the top of what was then called Hastings Hill (now Old London Road), where it meets Mount Road and Priory Road. The whole road took three years to complete, and another nine gates were installed through to Flimwell, with the next one on the south side of Battle. The Hastings-Flimwell turnpike Act was renewed in 1779, 1801, 1821 and 1849.

In 1814/5 the trustees spent a large sum on improving Hastings Hill, then one of the most difficult parts of the whole turnpike, creating Old London Road as it is today. Nearly a mile of the Ridge at Beauport was re-laid as a new road in 1824/5.

The Hastings-Flimwell turnpike reached its high point in the early 1830s, with the mushrooming town of Hastings generating much traffic, including daily London stagecoaches. But in the late 1830s the trustees’ income began declining following the construction of a new rival turnpike road which ran from St Leonards to the Royal Oak Inn at Whatlington via Silverhill and the Harrow - today’s A21.

These last miles of what is now the A21 were the child of the new town of St Leonards. Fashionable London architect James Burton had started building the new town of St Leonards in 1828, but it quickly became clear that the long travel time from London was deterring the well-off lodgers and house buyers that were needed. To reach St Leonards from London they had to travel via Hastings, then go up and over the difficult White Rock headland and along a rough track on the beach.

Burton saw an obvious solution: create a new shorter London road from St Leonards, going through Silverhill and the Harrow to Whatlington, and bypassing Hastings and Battle. The White Rock was removed in 1834/5, allowing Hastings and St Leonards to be linked with a seafront, but this was not enough for Burton. He was backed by many landowners between the Harrow and Whatlington who stood to benefit greatly from his new link north and south. Also popular was the branch road that was to run through Sedlescombe to Cripps Corner, giving access to towns and traders in north Kent.

But this St Leonards-based scheme was strongly opposed by the many Hastings-Flimwell trustees who owned land, shops and businesses in and around Battle. They believed the St Leonards turnpike would deprive them of valuable passing trade. So they set up a new trust that would shorten the Hastings-Flimwell road by making a link from Hastings town centre via Hollington to Beauport Park, cutting out Old London Road and the Ridge.

The battle over Battle – and the future layout of the main roads in the Hastings area – commenced in late 1835. Rival plans were drawn up and lively arguments took place, although these were somewhat clouded because a considerable number of people were hedging their bets by supporting both schemes at the same time. It was soon recognised that two turnpikes competing for the same travellers could both be financial failures, so a compromise was discussed.

On 27 January 1836 a meeting took place at Beauport Park, home of Sir Charles Lamb, which could have changed today’s road maps. Senior figures from all three trusts - including James Burton of St Leonards - agreed a compromise: the A21 idea should be dropped and the route through Battle upgraded. For trustees based in the town of St Leonards, there was little difference between the routes. But when the St Leonards trust met the next day they were told the compromise was unacceptable to their most powerful members, the rural landowners - especially Sedlescombe’s Hercules Sharpe - who would lose from it. So the St Leonards trust went ahead as originally planned, and today’s A21 was born as a result of a few people’s business interests.

Both schemes needed Parliamentary approval, which was given in 1836. The work on the two new ‘motorways’ began straight away.

The Hastings- Hollington and Battle-Johns Cross turnpike roads in red.

Until then travellers going from Hastings to Hollington would leave town by going over the Priory Stream bridge and following a rural track which wound up Dorset Place and followed roughly the line of today’s Bohemia Road to the crest of a hill just north of Silverhill junction. Then the lane dropped steeply down through woods and fields to the small village of Hollington, before meandering up the hill to the join the Ridge near the entrance to Beauport Park. The Hastings-Hollington trust spent the next two years replacing nearly all this with a new road.

Today’s gently sloping Cambridge Road was formed by cutting through the hill up to the Oval and laying the spoil at the town centre end of the works. Similar cutting, levelling and straightening took place all along Bohemia Road to Silverhill. Here the new Battle Road cut through the hill to the north, and a large straight embankment was laid right across the valley through Hollington village, brushing aside any buildings, lanes or environmental features in its way. The major road-making work, with cuttings and embankments, continued through to Beauport Park, to connect with the existing turnpike road. The new Battle Road was officially opened on 20 August 1838.

In addition, the trust built a new long straight road linking Battle and Johns Cross, today part of the A2100. All this was expensive. Over £12,000 had to be borrowed for the Hastings-Hollington section, plus another £14,500 for the Battle-Johns Cross section.

While this was going on, the rival St Leonards trust built two new turnpike roads coming out of St Leonards that met at Silverhill. These were London Road, from the seafront, and Maze Hill/Sedlescombe Road South, from the top of St Leonards Gardens. At Silverhill the two joined to form Sedlescombe Road North, which followed some of the old Harrow Lane and then became a new road to Whatlington, including a small tunnel under the Ridge (now a bridge). All these new roads opened in 1838.

The 1836 St Leonards- Whatlington turnpike roads, plus the 1839 extension to Cripps Corner via Sedlescombe, all in red.

So in just two years, 1836-8, the layout of many of the major roads in Hastings and St Leonards had been transformed, turning rural villages into urban suburbs, and opening up new areas of the town and surrounding countryside for large-scale development. And this had all been decided by a few local businessmen. Hollington became a centre for market gardens and dairy farms, able to supply the big town with essential food via the new road, as Ore had become a dormitory for the cheap labourers that were needed to build the new seaside resort

The new roads turned out to be much more costly than hoped, with landowners demanding large amounts for their land that was included in the roads. The St Leonards-Whatlington road was seriously delayed by a local dignitary (and Battle supporter) Sir Godfrey Webster who refused to sell the trustees a small piece of ground they needed. There was further conflict when unhappy mortgagees seized some of the tollgates on the Hastings-Flimwell road and retained possession for several years while they obtained a direct return from tolls.

The many turnpikes in and around the borough were very unpopular with the public, as each of them had at least one tollgate, making travelling expensive - five tolls had to be paid between Battle and St Leonards promenade.

Both these new London-bound turnpike schemes were financial disasters. They - like all Britain’s turnpikes, and the 1753 Hastings-Flimwell turnpike - were killed by the building of the railway network in the 1840s and ‘50s. The St Leonards-Whatlington trustees saw the danger coming, so in 1841 they obtained from Parliament one of the last of its turnpike Acts. They had already built a branch road through Sedlescombe to Cripps Corner, which opened in 1839, and the 1841 Act allowed them to extend this to Hawkhurst, from where travellers could reach what was then the nearest railway station, Staplehurst, on the London-Dover line. Sir Charles Lamb was the main funder of the Sedlescombe-Hawkhurst road. The Cripps Corner-Hawkhurst section opened in 1843, but three years later the railways reached west St Leonards from Brighton, fatally wounding all the turnpike roads in and around Hastings and St Leonards.

All the roads of the three turnpike schemes, highlighted on an 1850s Ordnance Survey map.

From 1852 all three railway lines coming to Hastings - from Brighton/Lewes, Ashford and Tunbridge Wells - were in operation, and passengers could reach London in just 2½ hours, a third of the stagecoach time.

From then on the turnpike roads were both financial losers and public nuisances. The gates and tollmen stayed in place, but road users saw little return on the cash they paid. At the end of 1867, when the Hollington road was on its death-bed, its accounts showed that in the 31 years it had been in existence, over a third of its spending was in paying interest on its borrowings.

In 1864 Parliament embarked on a positive programme of terminating all turnpike trusts, and from 1865 many Hastings-area people and organisations actively campaigned to have the local trusts abolished. This came to fruition on 1st November 1875 with the removal of 12 of the 13 toll gates in and around Hastings and St Leonards. Only the gate in Ore village survived, not being removed until the Hastings-Flimwell trust was officially wound up in 1880, when the gates on its more rural roads inland were also scrapped. From 1880 travellers could go from Hastings to London free on the roads.

The Tower Road/London Road tollgate and gatehouse in 1865.

The St Leonards Gazette commented on 27 November 1875 "A more stupid or vexatious system for collecting the funds necessary for constructing and maintaining the highways could hardly have been invented." It was "a system that had in it so much that was evil and so little that was good. ... The existence of this long-standing absurdity has been a disgrace to our boasted civilisation."

But although the turnpike roads had been very unpopular in their final decades, they were to play key roles in the history of Hastings and St Leonards by setting up a framework of transport and communication routes to the west and north of the town along which development could take place, and by improving the road link to London.